Explore the Erie Canal: Black Rock & Buffalo

A Tale of Two Villages

By Mary Durlak

On October 31, 1821, a rain storm on Lake Erie caused Captain Rogers of the steamboat Walk-in-the-Water to give up efforts to reach the shelter of Point Abino on Lake Erie. He turned back toward safety in Buffalo. As the storm worsened, the captain anchored in the lake, but the steamboat was taking on water. By 4:30 a.m., the passengers were on deck preparing for the worst. Mary Witherell Palmer, who had boarded the boat in Black Rock at 4:00 the previous afternoon, was among the passengers; many did not expect to live to see the dawn.

Captain Rogers pulled up anchor in hopes that the boat would be washed up on shore. It was. The boat hit land with such force that it was “fixed immovably in the sand” while the waves washed over the decks. When dawn broke, a sailor helped the passengers reach solid ground. Carriages took the passengers, all of whom survived, to the Landon House, a hotel in Buffalo.

No Obvious Choice

The wreck of the Walk-in-the-Water demonstrated one argument against choosing Buffalo as the western terminus of the Erie Canal: Lake Erie’s sudden, fierce storms. But, more importantly, Buffalo did not have a harbor. Great Lakes ships sailing to Buffalo had to anchor in the lake and transport goods to the village on smaller vessels; Buffalo Creek was blocked by a sandbar that prevented the entry of anything but the smallest boats.

However, the Walk-in-the-Water also demonstrated one of the major arguments against choosing Black Rock. According to Mary Palmer, who was also on the steamboat’s first voyage, the power of its engine plus 16 yoke of oxen—32 oxen—were necessary for the boat to be “hauled up the rapids” from Black Rock to Lake Erie. William Hodge described the Niagara River between Black Rock and Lake Erie as “…rolling and whirling as if in haste to make the great leap over the grand precipice.”

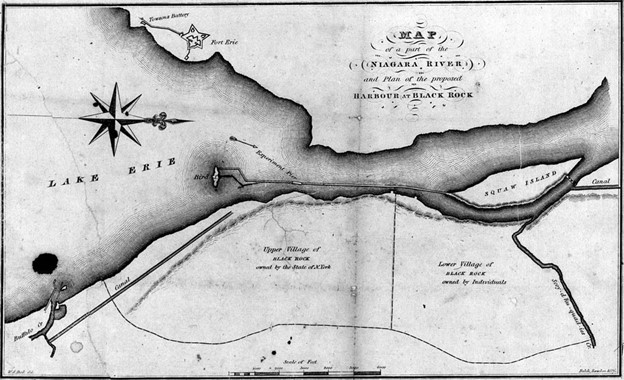

Black Rock, three miles from Buffalo, had a small harbor sheltered by today’s Unity Island and Bird Island. A natural wharf created by an outcropping of black rock projected into the Niagara River just north of today’s Peace Bridge. However, reaching Lake Erie meant traveling through those rolling, whirling rapids. And the point of the canal was to reach Lake Erie.

A Long Debate

The first debate about the site of the canal’s western terminus was between Oswego on Lake Ontario and an undetermined site on Lake Erie. Peter Porter, a Black Rock businessman whose company operated the portage around Niagara Falls, favored Oswego. However, decision-makers in Albany favored a route wholly within New York State, a sentiment that solidified after the War of 1812.

The Buffalo-Black Rock rivalry was already underway by 1810. Joseph Ellicott had been named resident-agent of the Holland Land Company in 1800, and the fledgling village of Buffalo was to be the company’s major settlement. He recognized at the time that they needed to improve Buffalo’s harbor. In 1815—two years before digging the Erie Canal began—Buffalo asked New York State for funds to build a harbor. Meanwhile, Black Rock had developed not only a functional harbor but also a well-established shipbuilding industry.

Engineers Uncertain

In the absence of an unmistakably superior site for the western terminus, the engineers waffled, and the feud between the two villages grew fierce. Buffalo was named the terminus in 1816 by the state-appointed canal commissioners. William Peacock, a close associate of Ellicott’s who served as engineer and surveyor, submitted an engineering report favoring Buffalo in 1819. His report proposed building a 1000-ft pier into Lake Erie, arguing that such a pier would prevent the sandbar from forming and blocking the entrance to Buffalo Creek.

In 1819, New York State offered Buffalo a $12,000 loan to build a harbor, but the loan had to be secured for twice its value. If Buffalo was chosen as the terminus, the state would forgive the loan. At first, nine men agreed to put up their personal funds, but a financial panic left only two willing to take the risk. Samuel Wilkeson joined them; a one-time shipbuilder, he took over the construction of Buffalo’s harbor in 1820 when the hired project manager failed. Perhaps due to the uncertainty of Buffalo’s success in financing and building a harbor, the canal commissioners reported in 1820 that a final decision on the terminus was premature. By 1821, under Wilkeson’s supervision, Buffalo had built a 1200-ft pier.

Still, in 1822, the major engineers of the Erie Canal were in disagreement about the terminus. Perhaps as an effort to reach a decision—the canal’s Deep Cut at Lockport was already under construction—the canal commissioners gave Black Rock a chance to eliminate the problem of the Niagara River rapids by building an “experimental pier.” However, that same year, it became clear that the canal would extend to Buffalo regardless of which village was named the official terminus. The commissioners authorized a canal from Buffalo toward Black Rock. In 1823, Buffalonians dug the canal with enthusiastic optimism.

Political Winds Shift

But, in 1823, Clinton was no longer governor, and his political rivals controlled appointments to the canal commission. The commission met in Black Rock in June 1823 and voted to accept Black Rock as the terminus. Clinton, who had served as a canal commissioner since 1810, was removed. But that move backfired. New Yorkers, who recognized that Clinton was the driving force behind the construction of the now-popular canal, held massive rallies supporting him. He was easily re-elected governor in November 1824. And in February 1825, the New York State legislature directed the canal’s engineers to “continue and complete the Erie canal to Lake Erie at the mouth of Buffalo creek, distinct from, and independent of, the basin at Black Rock…”

Eight months later, the Erie Canal opened. Governor De Witt Clinton boarded the Seneca Chief in Buffalo for its celebratory voyage to the harbor of New York City. And, within a year, the ice-laden spring flow of the Niagara River destroyed the Black Rock pier.

Special thanks to The Black Rock Historical Society for providing assistance in bringing historical details together. Learn more about their work at https://blackrockhistoricalsociety.com/

References

The Wreck of the Walk-in-the-Water, pioneer steamboat on the western lakes; by Mary A. Witherell Palmer, communicated to the Buffalo Historical Society in 1865

Papers Concerning Early Navigation on the Great Lakes: The Pioneer Steamboats on Lake Erie, by William Hodge (1883)

Joseph Ellicott and the Holland Land Company; The Opening of Western New York, by William Chazanof (1970)

Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation, by Peter L. Bernstein (2005); p. 288–290

Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire, by Gerard Koeppel (2009)

History of the Canal System of the State of New York Together with Brief Histories of the Canals of the United States and Canada: Part One, Chapter II, Building the Erie (1906), by Noble E. Whitford

Map: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1829_Black_Rock_Harbour_map.jpg

Exploring the Erie Canal programming is free to the public thanks to the generous support of Humanities NY, The Erie Canalway Heritage Corridor, and the National Endowment for the Arts.